Are central banks issuing digital banking licences to counter the threat of fintechs and big techs?

By Ellen Hardy

Technology has enabled the world of finance to innovate and diversify rapidly in recent years with the increasing digitalisation of banking services — and regulators have struggled to keep pace until now

- Four of the leading Asian markets: Singapore, Hong Kong, Australia, and China, have all adopted strong digital licence frameworks, with other countries in the region watching closely

- Regulators have highlighted a desire to work together to establish global standards, although to date, different countries have been notable in implementing their own distinct regimes

- The elephant in the room remains whether regulators will allow Chinese giants such as Tencent and Ant Financial to enter their markets, and how they are going to manage the ambitions of big tech firms such as Facebook, Google, and Apple

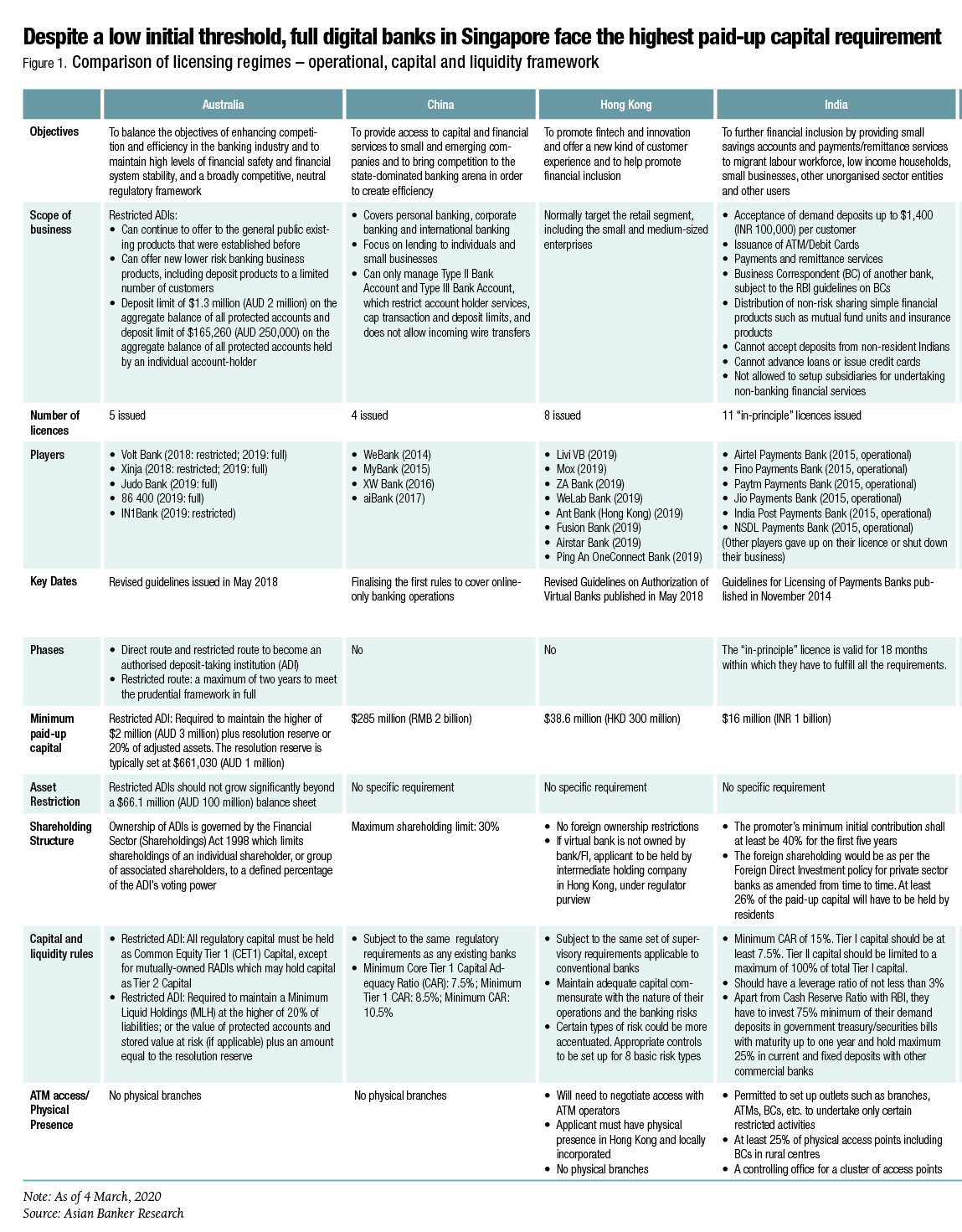

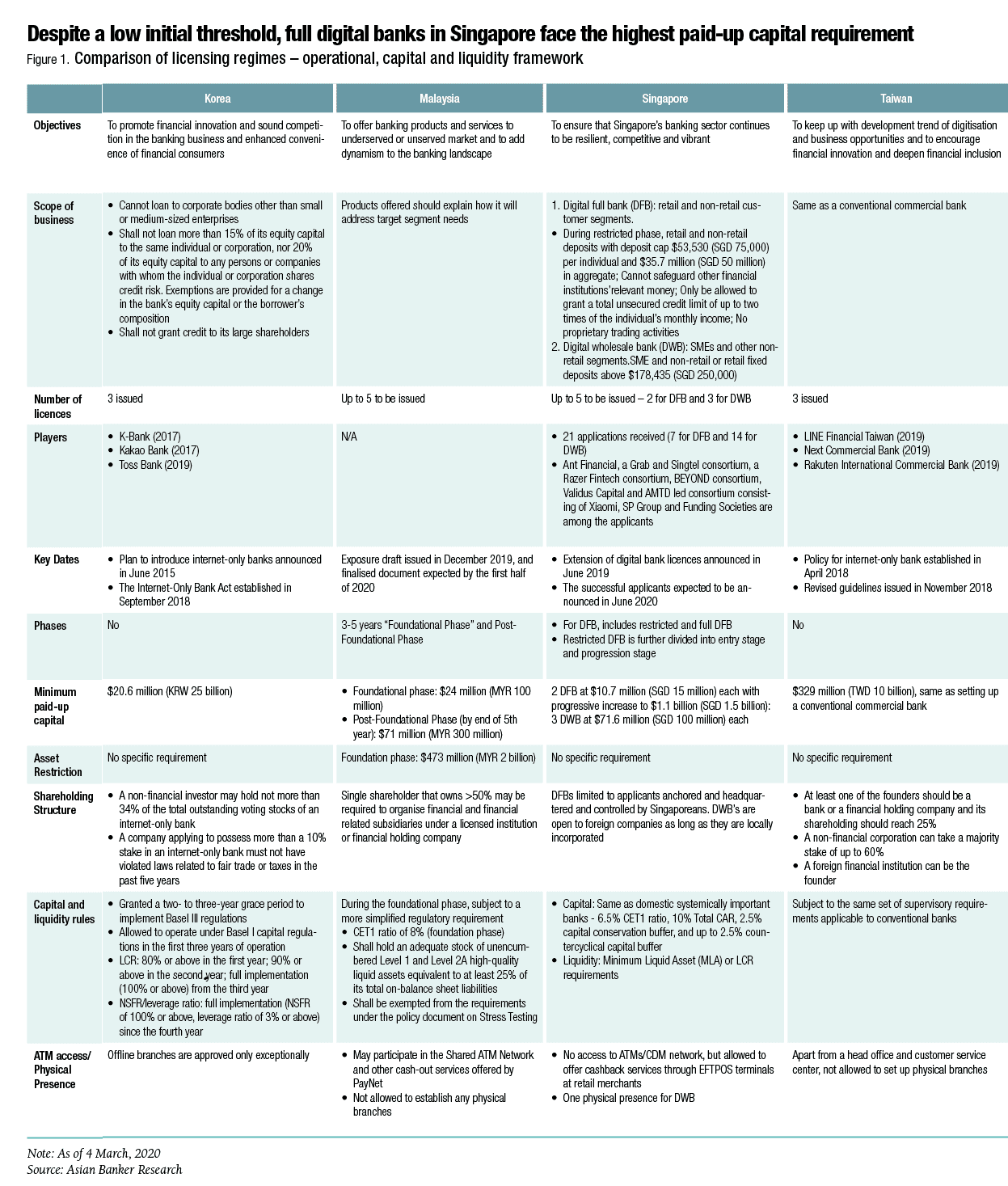

Four of the leading Asian Markets — Singapore, Hong Kong, Australia and China — have all adopted strong digital licence frameworks, with other countries in the region watching closely. Regulators on the other hand, have highlighted a desire to work together to establish global standards. Although to date, different countries have been notable in implementing their own distinct regimes. However, it remains to be seen whether regulators will allow Chinese giants such as Tencent and Alibaba’s Ant Financial to enter their markets, and how they are going to manage the ambitions of big tech firms such as Facebook, Google, and Apple.

As central banks begin issuing digital-only banking — also known as neo, virtual, and challenger banks — licences across the Asia Pacific region, questions are being raised about whether they are doing this to keep the ambitions of big tech firms, such as China’s Tencent and Alibaba, and US tech giants Facebook, Google, and Apple at bay.

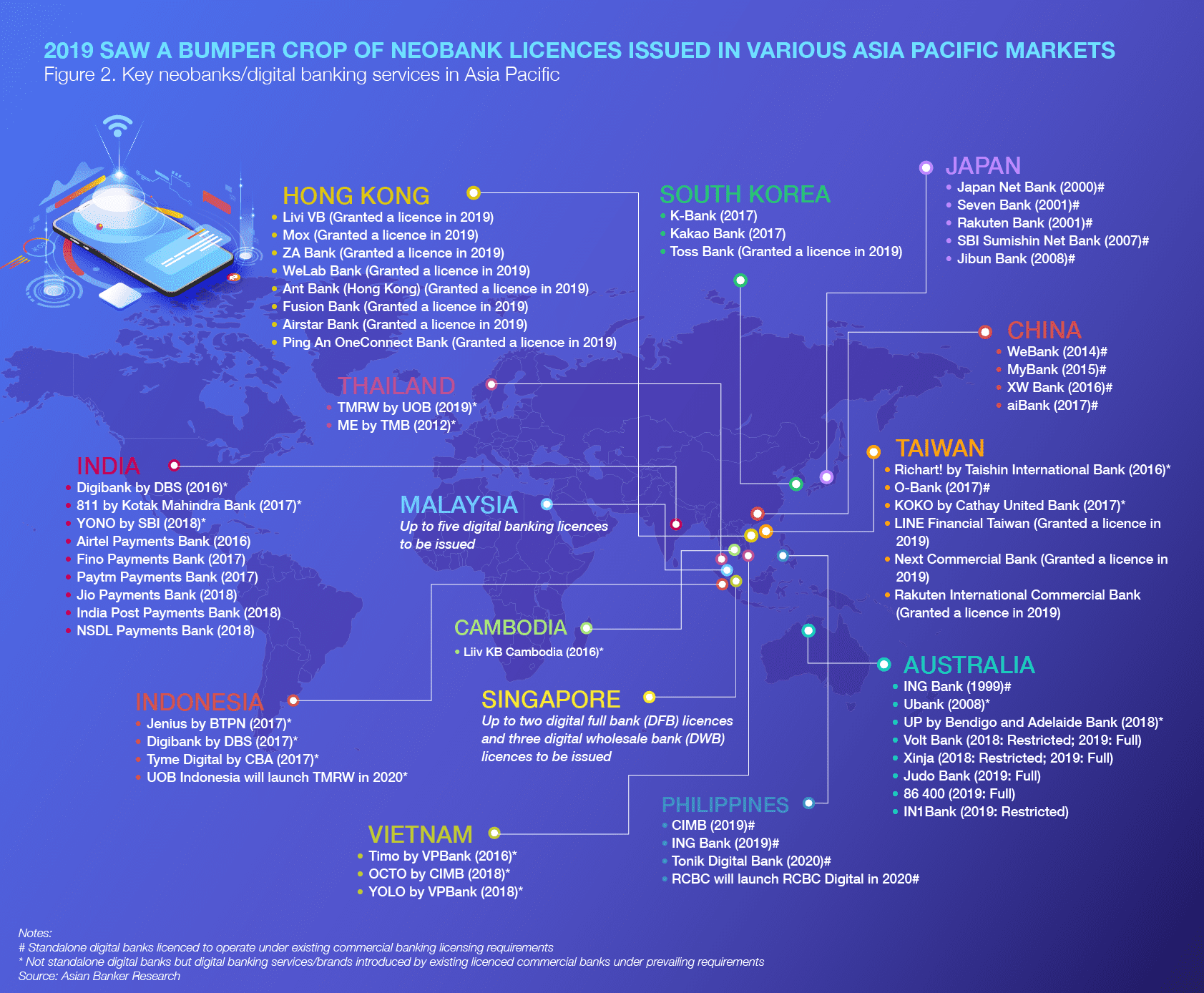

Financial regulators in Australia, Hong Kong, China, India, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have all recently issued such new forms of licences, while Singapore and Malaysia are in the process of doing so. The first internet bank in Japan, Japan Net Bank (Paypay Bank), began operations in early October 2000, driven by financial deregulation in the 1990s. Other internet banks that were established such as Rakuten Bank and SBI Sumishin Net Bank, are operating under existing commercial banking licensing requirements. LINE Financial and Mizuho Financial Group established a joint venture in May 2019 to prepare for the launch of a new digital-only bank by this year.

In Southeast Asia, Malaysia has issued its draft digital licensing framework, offering up to five digital licences for conventional and Islamic banks, while the Philippine central bank issued a rural banking licence for Tonik Digital Bank, the first pure-play digital bank in the region, to start business this year alongside existing virtual institutions CIMB Bank and ING Bank. Both CIMB Bank and ING Bank have commercial banking licences and have a digital platform business model with minimal physical touch points through partner merchants. Once the virtual banking regulations have been released, the current digital banks will be given one year as a transitional period to comply with the regulations in order to get the virtual banking licence.

Authorities in Thailand are trying to keep pace with their Asian counterparts, with the governor of the central bank recently saying that it is looking to introduce digital lending and other services this year to promote competition and meet the needs of its underserved banking population. Vietnam has also indicated that it is likely to explore regulating digital banks in the near future.

In a study of digital bank licence holders and regulators in Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia and China to survey the virtual bank landscape, significant opportunities exist for this new area of digital finance — but they appear geared towards countering competition from big tech competitors entering the financial markets.

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

HKMA takes an active approach while avoiding the China question

Hong Kong is catching up with China when it comes to online disruption of finance, with its regulator, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), taking the approach that the system can absorb the pressure of increasing competition. In contrast to other markets, it is notable that two of the winning licence bids are joint ventures led by two major incumbent banks, namely, Bank of China (Hong Kong) and Standard Chartered, which are also two of the territory’s three note-issuing banks.

It has been argued that some Chinese fintechs are seeking to use a Hong Kong digital banking licence as a springboard to expand into other Asian markets. In fact, many would be leveraging off their access to southern China’s Greater Bay Area to create scale for their Hong Kong operations, and that governments in the region are keenly aware of this. Hence, their position in the virtual bank market is critical, as it has been estimated that some 30% — $15 billion — of Hong Kong’s total banking revenue could be up for grabs.

As of 9 May 2019, the HKMA had issued banking licences to eight organisations, comprising joint ventures (JV) and consortia of mainly banks, telecommunication and technology companies, to operate as virtual banks.

The first batch of three licences was issued at the end of March to Livi VB Limited (JV between Bank of China Hong Kong, JD Digits (formerly JD Finance), and Jardines), Mox Bank Limited (JV of StanChart, PCCW, HKT and Trip.com) and ZhongAn Virtual Finance Limited (owned by ZA International).

In subsequent announcements, another five licences were granted to WeLab, Ant SME Services (Hong Kong) Limited (owned by ANT Financial), Infinium Limited (JV between Tencent, ICBC and Hillhouse Capital), Insight Fintech HK Limited (JV between Xiaomi and AMTD Group) and Ping An OneConnect Company Limited (owned by Ping An).

Simon Loong,

Founder and group CEO of WeLab

Norman Chan,

Former chief executive

HKMA

Simon Loong, founder and group CEO of WeLab, expressed his satisfaction in receiving one of the licences granted by HKMA, “We are very proud that we are the only local fintech company in Hong Kong to be given a licence. We have 200 very experienced people in WeLab virtual bank. And we have Professor KC Chan, former secretary for financial services and the treasury of Hong Kong and former dean of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, as chairman of the bank and senior advisor to WeLab. This is a validation of our business model and industry standing. It will help open doors for our future relationships and to new markets.”

This means that WeLab has now gained entry into the retail banking market.

“The virtual bank licence in Hong Kong is exactly the same as for the commercial banks. There are no different classes of licences or restriction on activities based on whether it is a fintech, commercial bank or consortium that holds the licence. The licenced banks are not subject to a test period before they become fully operating banks. There is also no restriction and cap on taking deposits and banks can launch any retail banking products and services, even join the existing ATM networks. The greatest advantage is that it allows banks, through agreement between Hong Kong and Beijing. to access the 70 million population of the Greater Bay Area,” stated Loong.

Norman Chan, former chief executive of the HKMA, sees the launch of virtual banks as a key component of its Smart Banking Initiatives that facilitate financial innovation, enhanced customer experience and financial inclusion in the territory.

The HKMA says it will closely monitor the operations of virtual banks after they have commenced business, including customers’ reactions to the new modes of delivery of financial services as well as the impact, if any, of these virtual banks on the banking sector in general. The HKMA expects to be able to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the situation about one year after the first virtual bank has launched its service.

It added that it “adopts a risk-based and technology-neutral approach to banking supervision,” which means that, when developing regulatory frameworks, it “will only base on the intrinsic characteristics of the financial activities or transactions, and the risks arising from them”.

The regulator is keen to oversee the growing use of artificial intelligence, recently publishing a set of high-level principles on the use of the technology. This comes on the heels of questions about the effectiveness of HKMA’s fintech sandbox, set up in 2016, which has been accused of helping banks experiment with fintech possibilities rather than help new players enter the market.

Developing a whole new banking model, not simply a digital bank

To incumbent banks, the new virtual banking licence means adopting a new way of operating. “The introduction of digital banking licences marks a convergence of two trends, commercial banks wanting to be technology companies and fintechs seeking to be licensed to operate the full range of commercial banking businesses under proper regulatory and governance requirements. So we are combining a nimble technology infrastructure with a new business model,” stated Loong.

Deniz Güven,

CEO,

Mox Bank Limited

Melisande Waterford,

GM of regulatory affairs and licensing

APRA

Deniz Güven, CEO of Mox, Standard Chartered’s new virtual bank venture in Hong Kong, said that it began researching the project 18 months ago and focused on building it around customer pain points instead of products and consumer behaviour instead of demographics.

“Whether you call it a digital or virtual or neo bank, what we are trying to build is the future operating model. We are trying to build a new company and a new culture,” he said. “The aim of the digital bank is building services instead of products. We are not going to sell a plastic card, but a service from end-to-end to solve pain points affecting customers right now.

Güven believes that if the new virtual bank wants to be impactful and change the market, it has to focus on a new operating model. He noted that the bank’s priorities are customer onboarding within five minutes, being cloud-based, while maintaining prudent risk frameworks, policies, and culture. His staff now numbers 160 people — half of whom are engineers.

In terms of services, Güven said that one of the features of the virtual bank will be the way it is building together and leveraging the strengths of JV partners, PCCW, HKT and Trip.com.

“We are thinking about how we can acquire customers and create a new customer end-to-end acquisition model with our partners, not simply creating traffic,” he said.

He also hinted that a digital bank model was being built with a view to exporting to other markets in the future. “Currently, we have a laser focus on Hong Kong. After that, it’s impossible to say where next. But with what we are building from tech and value proposition standpoints, everything is possible,” revealed Güven.

Australia looks to bring independent players into the fold to challenge its “big four”

Meanwhile, Australia has taken a different tack, with the banking regulator providing licences to new, independent players, in part to provide more competition for the “big four” banks that dominate the country’s finance market and which were roundly criticised in the 2017 royal commission inquiry.

For their part, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has said that while it wants to encourage competition, it has no intention to treat challenger banks any differently from other deposit taking institutions. “It’s not APRA’s role to pick winners and losers,” said Melisande Waterford, general manager of regulatory affairs and licensing. “APRA is keen to see new entrants succeed. APRA’s licensing ‘mission’ is not to license as many new banks as it can, as quickly as it can. Rather, our mission is to facilitate the launch of viable entities.”

The fourth licensee under APRA’s scheme, Xinja, was granted its licence in September, joining Volt, Judo and 86 400. ING Bank became the fifth licensee, having been granted a licence in December 2019.

Xinja CEO and founder Eric Wilson said that the regulatory process was stringent. In order to navigate the regulatory process, he hired a number of key staff who had previously worked at APRA.

Eric Wilson,

CEO and founder,

Xinja

Ross Buckley,

Professor,

University of New South Wales

“There were months where more than 60% of our staff were working on materials for our regulators in one form or another, aiming for the full licence. It’s probably cost us well in excess of $3.9 million (AUD 6 million) in salaries and consultants,” he said.

As the only 100% cloud-based bank in Australia, Xinja is aware that people will be watching how it tackles data privacy and emerging mobile security threats.

“We try to make our customers aware and not be afraid of our respective data and privacy obligations. Being a digital bank, our customers need greater confidence that their data and privacy are being respected and protected so they feel genuinely safe banking with us. Ultimately, we hope to offer configurable security options to give our customers more control,” Wilson said.

Wilson added that starting from nothing means Xinja has been able to build many of the necessary compliance controls into the core products and experiences. They’re also seeking to build gamification to their products, rejecting “poorly segmented marketing messages” in favour of a model where “personalisation has to become the product”.

These are issues that are not being properly addressed by the “big four” in Australia, said Ross Buckley, a professor at the University of New South Wales. He believes that the new wave of challenger banks poses an “existential threat” to their market dominance, especially in light of the royal commission that rocked public confidence.

“The simple fact is that a fintech can assess credit better than any bank, as well as the advantages of a lower cost business model,” he said. “Banks are not coming to terms with the fact that in 200 years, banking has been a customer game, but now it is a data game. If Facebook got its payment system up, a major Australian bank could be in trouble within 18 months.”

Buckley also said that he fears that not only is Australia’s digital banking sector well behind China’s, but that the regulators do not have the institutional understanding to be able to keep pace with technology.

Chinese fintechs continue to lead the world in imagination and scale

As different jurisdictions look to embrace the digital banking future, it’s indisputable that everyone has one eye on the big Chinese players. The mainland has led the region generally, with four virtual banking licences issued since 2014.

To look at the pioneering leadership of WeBank, one of the original licence holders, is to understand why many fear its ability to completely shake up any new market that it enters. Alan Ko, head of fintech innovation at WeBank, agreed that his organisation takes a proactive approach to its operations.

“We work closely with our regulators to understand their requirements as well as the pain points, and co-build solutions to address them through regtech. For example, we have set up the Mailuo, a regulatory big data platform for the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), which includes risk index monitoring and fund flow tracking systems. We have also built a financial regulatory big data platform, a smart suggestions platform, and online voting and decision-making platform for Shenzhen Municipal Financial Service Office.”

WeBank’s approach to regulation is to not wait to be told what safeguards should be put in place, but to show regulators that they are working on key challenges such as system integrity for peak transaction volumes that last totalled more than 300 million per day.

“Our explorations-based API banking strategy is to connect more industries and scenarios, embedding our banking services into different contexts and provide seamless user experience to our customers,” he explained.

Alan Ko,

Head of fintech innovation,

WeBank

Fernando Restoy,

chairman,

Financial Stability Institute,

Bank for International Settlements

In terms of fintech, Ko said that its strategy remains with investing in AI, blockchain, cloud computing, and big data — not only to support the business, but also to build fintech ecosystem on top of these technologies. To put its scale in perspective, it has released 10 open-source applications , while its big data platform houses over 15 petabytes of data, with over 300 thousand batch jobs processed daily.

WeBank has remained coy about its intentions to move beyond the mainland, but Ko noted that in 2019 when it joined the Singapore FinTech Festival, it generated quite a lot of interesting conversations with the fintech communities around the world”.

Singapore takes a strong stance on profitability, capital, and IT controls

With Chinese fintechs such as WeBank taking a keen interest in Singapore’s digital banking potential, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) announced the biggest shake up to its financial sector in two decades, with the introduction of up to five new digital bank licences.

The scheme will enable non-financial players such as tech and e-commerce companies to offer banking services. Two of the five licences will be ‘full bank’ licences, which will include the ability to take deposits from retail customers, while the remaining three will be digital wholesale licences to serve small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and other non-retail segments.

MAS said that it has been driven to license virtual banks because of the “unique value propositions and to add diversity and choice to the market”. Of the countries which have so far entered this regulatory sphere, Singapore has established some of the toughest licensing requirements.

Entrants already face much stiffer rules than in markets such as Hong Kong, such as the requirements for full digital banks to have $1.5 billion in capital as well as local control. Any new digital banking organisation may also face margin pressures, as MAS expects it to attract customers by offering more attractive deposit and lending rates than the incumbent banks.

“They may have access to more wide-ranging data sources and may adopt different credit risk assessment approaches to lend to under-served segments, such as the young and micro enterprises,” a spokesperson for MAS said. “These new digital challengers will also provide competition to spur existing banks to continue to improve on their digital offerings.”

MAS said that it received 21 applications across the two schemes, with seven for the digital full bank (DFB) licence and 14 for the digital wholesale bank (DWB) licence. It will announce the successful applicants in June 2020, and they are expected to commence business by mid-2021.

According to MAS requirements, a DFB will commence operations as a restricted DFB before becoming a full functioning DFB. The pace of growth of a restricted DFB will depend on its ability to meet its commitments and MAS’ supervisory considerations.

However, it generally expects a DFB to be fully functioning within three to five years from commencement of business.

At the commencement of business, a DFB will have to meet minimum paid up capital requirement of $11.13 million (SGD 15 million) and deposit caps of $37.1 million (SGD 50 million) in aggregate, $55,650 (SGD 75,000) per individual and limit its scope of customers from whom it can solicit deposits. The minimum paid up capital requirements will be progressively increased to $1.1 billion (SGD 1.5 billion) and the deposit caps will be eventually removed when it becomes a fully functioning DFB.

Among the more notable of the 21 bidders who have joined the race for the five digital banking licences are Ant Financial; a Grab and Singtel consortium, which is owned 60% and 40%, respectively by the region’s leading ride hailing and “super app” provider and telecommunication group and a Razer Fintech consortium which is 60%-owned by the subsidiary of the Singapore-based global e-gaming group Razer Inc. with strategic equity partners that include Sheng Siong Holdings, FWD, LinkSure Global, Insignia Ventures Partners and Carro. It has announced plans to launch Razer Youth Bank aimed at younger customers.

Other bidders include the BEYOND consortium led by V3 Group and EZ-Link, and partners such as Far East Organization, Singapore Business Federation, Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance and Heliconia Capital Management; Validus Capital, a local SME financing platform, supported by Vertex Ventures and Dutch development bank FMO; and a consortium led by UK-based Enigma Group and partners that include Singapore-based companies, Qrypt Technologies, 2359 Media and Blockchain Worx.

The consortium model emerged as a key trend after MAS advised that applicants must demonstrate how their large user bases can help them generate profits if they were to win a licence. They have apparently also taken into account the national interest when considering the licence application.

Global regulator sends warning to big tech companies

In general, regulators are trying to balance the benefits of a digitised, globalised world with the integrity and stability of the financial system. Fernando Restoy, chairman of the Financial Stability Institute at the Bank for International Settlements, outlined a number of key challenges that need to be considered when designing an adequate policy framework to safeguard the orderly modernisation of the financial industry on a global scale.

“Central banks do not typically have a mission to directly promote the digitisation of financial institutions. They should however contribute to efforts — together with other authorities — to adjust or set up a proportionate regulatory framework. The key challenge here is to maximise the benefits new technologies could bring while preserving the stability and functioning of the financial system,” Restoy said.

He noted that the principle ‘same activity, same regulation’ has been frequently used to stress the need for a level playing field between new fintech and big tech companies and traditional banks, however it must be acknowledged that different types of institutions generate different risks when performing the same activity.

“Arguably, the risks created for the financial system not only depend on the activity per se but also on the combination of different activities on the balance sheet of an institution,” he added.

Critically, in setting the tone for regulators, Restoy stated that “activity-based regulation cannot entirely substitute entity-based regulation”. This appears to be a shot across the bows of big tech firms, such as Alibaba, Apple, Facebook, and Google, who are increasingly active in the banking and finance markets, and who by and large have been arguing to regulate the activities that they conduct in the space rather than licensing them as institutions.

And while these new licensing regimes will offer clarity and opportunity, they cannot solve the fact that the lines between technology organisations and financial institutions continue to become increasingly blurred.

But no matter who is doing the innovating, both regulators and the banking and finance industry should take note of the lessons learned from some of the problematic tech unicorns: namely that the people policing the standards will often be several steps behind the disrupters.

Categories: Risk and Regulation